Healthy Outlook: Q+A With MASS Design’s Michael Murphy

It’s been a busy decade for Michael Murphy, founding principal and executive director at MASS Design Group (Boston), a not-for-profit firm of more than 200 architects, landscape architects, engineers, builders, furniture designers, and researchers.

It’s been a busy decade for Michael Murphy, founding principal and executive director at MASS Design Group (Boston), a not-for-profit firm of more than 200 architects, landscape architects, engineers, builders, furniture designers, and researchers.

Since he keynoted the Healthcare Design Conference + Expo in 2013, he and his firm have finished a number of projects in Rwanda, including two national medical facilities, a new biomedical research facility, and three university projects. The firm’s first federally qualified health center in the U.S. opened in McKinney, Texas, last year.

Additionally, Murphy co-authored with Jeffrey Mansfield, design director at MASS, the newly released book “The Architecture of Health: Hospital Design and the Construction of Dignity,” published by New York’s Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. The book complements an exhibition at the museum, “Design and Healing: Creative Responses to Epidemics,” which runs through Feb. 20.

Healthcare Design talked with Murphy about his latest projects, how historical architecture holds lessons for the industry, and his future hopes.

Healthcare Design: Where did inspiration for this book come from?

Michael Murphy: Since our first healthcare project in 2011, in Butaro, Rwanda, I’ve been consumed with how hospitals offer us so many lessons on how fundamental architecture is to our ability to live healthy lives. I’ve looked at historical eras and how different architects have solved these questions and wanted to compile this into an abbreviated history.

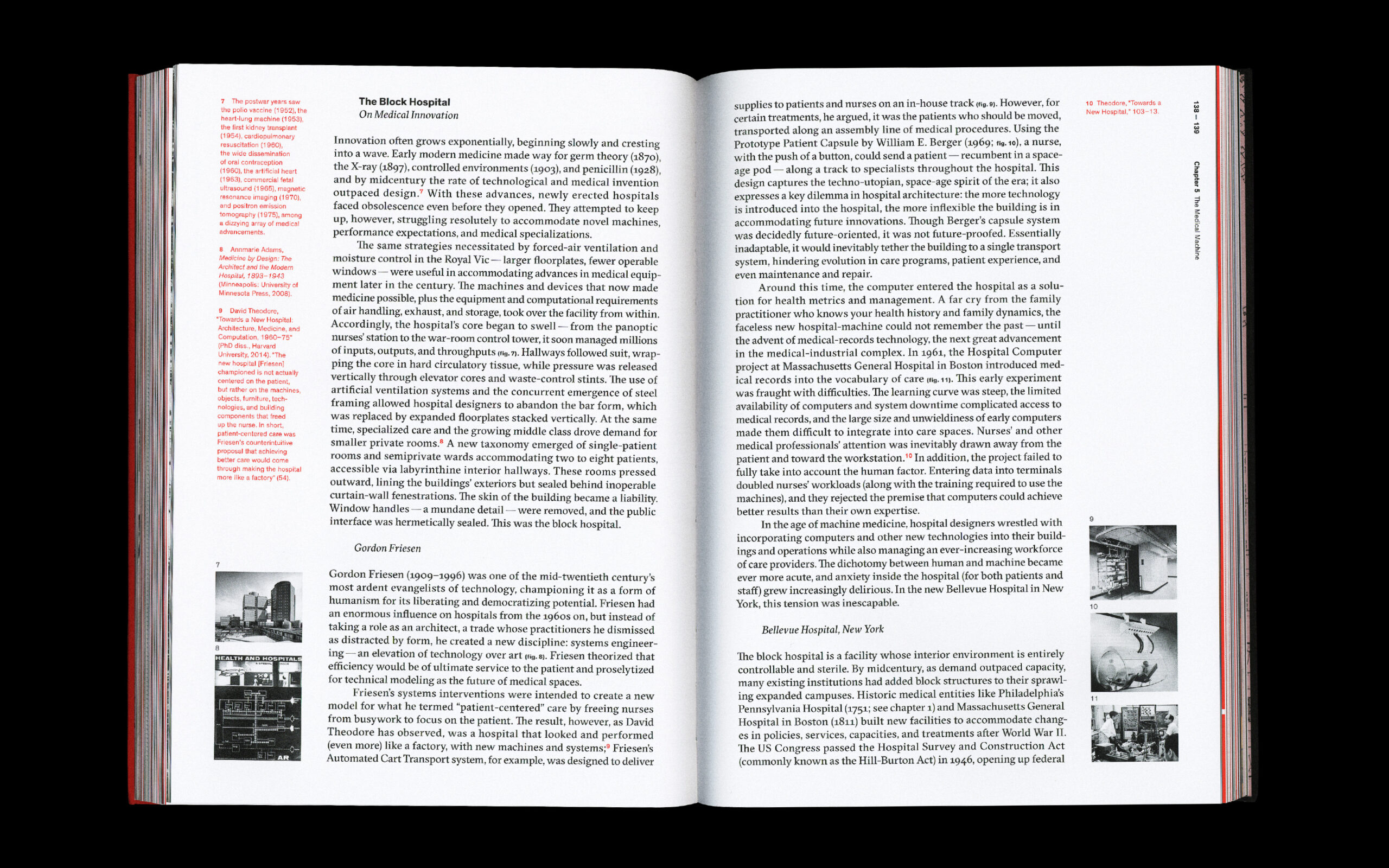

The pandemic has only expedited the need for such a survey, one that asks how architecture can more broadly allow us to breathe better and remain healthy. Hospitals are a window into how to answer that question because they are constantly thinking about the quality of indoor air environments and infectiousness.

Is there one historical design lesson in the book that stands out to you?

Probably the number one lesson is that buildings must breathe. And I say that from an airflow standpoint, but also from a standpoint that these structures are living breathing organisms that can change us, and change with us.

The book title introduces the idea of the relationship between the built environment and dignity. Why is that connection important?

We argue in the book that hospitals are always attempting to mitigate the space between treating the individual and recognizing their dignity and managing massive population health issues, like outbreak and complicated medical procedures. Often between the two extremes is where design emerges to navigate the differences between an institution and feeling institutionalized. That feeling of hospitality is where dignity emerges—and is absent from so many medical spaces.

Why did you start your book with a look at Prentice Women’s Hospital, an iconic project in Chicago that closed in 2011?

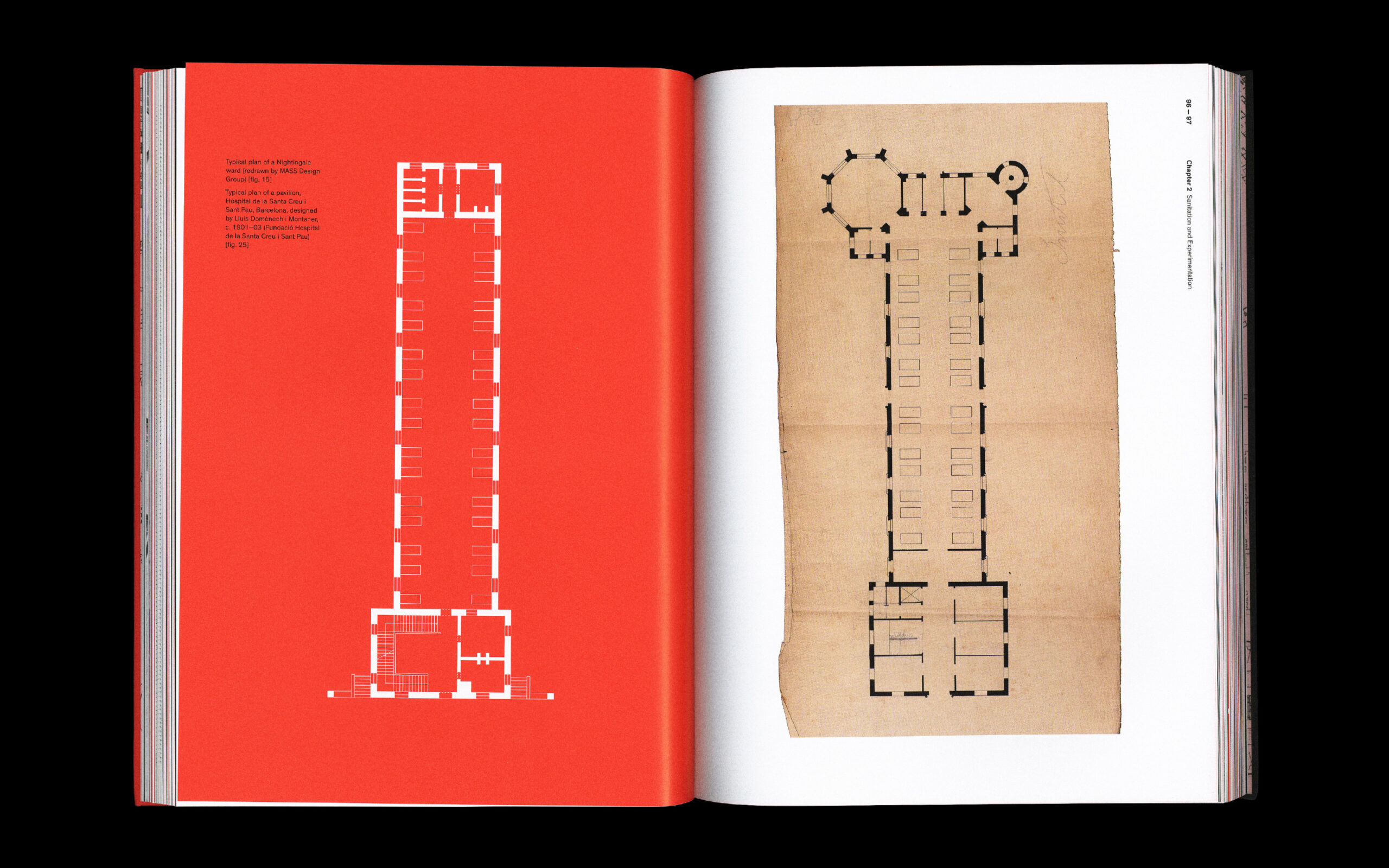

Prentice is a strong example of how hospitals can be designed from the inside out to respond to idealized parameters of care, such as the relationship and distance between the nurse/staff and the patient. In Prentice, the quatrefoil structure was based on this number that architect Bertrand Goldberg was analyzing and the idealized geometry that optimized it—in this case, a semicircular form around a nursing station. While Prentice eventually was demolished because it was hard to adapt, it does show how the DNA of hospital design is always infused with ideas of health outcomes and behavior-shaping strategies.

In one chapter, you write: “… The forms and functions of our built world are not fixed. Architecture must adapt to unknown futures and, over time, serve the lives of many publics.” How is the industry rising to this challenge?

I think to date the industry has been decentering the hospital to take on more community-based centers, urgent care centers, and at-home medicine. But at the hospital itself, I think we have work to be done.

The assumption has been that ever more flexible space is the answer, but when flexibility is prioritized over all else, purposeful, bespoke design solutions have to be abandoned. While that might serve the institution’s needs, it fails to serve the needs of the staff and patients, who want to know their daily experience, their health, and their workplace is what is being designed for. So I actually believe we need more fixed spaces that we’re open to fully changing in faster increments, than flexibility above all else.

The book discusses past epidemics alongside the evolution of architecture. What impact do you think the current pandemic will have?

The pandemic is already shaping how the public thinks of the buildings around them. The use of outdoor waiting, social distancing, and new air handling mitigation systems in all typologies suggests that our health as a priority in buildings has migrated beyond the hospital into other building types. I think new policies will emerge that demand higher airflow rates and more access to windows and operable fenestration. I hope that those changes begin to thin out and shrink floor plates, and remind us of some of the lessons of medical facilities from a century ago for how to adapt.

How does human-centered design lead to better environments for patients and staff?

The one size fits all solution is universally designed for no one. Meaning, one might use the facility but not feel like it meets their specific needs. Human-centered design challenges this notion by putting humans and their experience first and at the center. Hospitals push hardest against this because they have very real functional, code-based, legal, and population health requirements to operate effectively, often which treat individuals as numbers. So human-centered design is always in tension in medical spaces, which is what makes them so fascinating. But I hope the human-centered designs start winning out more.

What’s one takeaway in your book for the design community?

That hospitals have been an understudied and undertheorized typology of architecture, and that by studying them, we learn more about the foundational workings of architecture than by looking at other typologies that are less complicated. Hospitals are uber-architecture. They reveal all the complexities and hope of the discipline and make us realize how essential good design is for us to live a full and healthy life.

You were interviewed recently on 60 Minutes, talking about your work and community-focused architecture. Why is it important to reach the broad public with the importance of this message?

The public still thinks of architecture and architects as an extra service for the wealthy, instead of a fundamental service for the society to function. During the pandemic it became clear that buildings shape not just our health, but our rights as citizens to have access to air. And that reckoning liberates architects from being in the service of those who can afford it into being in the service of our rights as a society.

The release of your book accompanies an exhibition at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Tell us about that.

The show began before the pandemic, and it was about these questions of how design and health shape us and our society. The pandemic only reinforced this thesis and in real time we had examples we had to include. We shifted and redesigned the exhibit so we could have both current and historical examples narrate our daily lives as we lived through the pandemic.

We shifted and redesigned the exhibit with Ellen Lupton, senior curator of contemporary design at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design, and her team, so that we could have both current and historical examples narrate our daily lives as we lived through the pandemic. Some of my favorite pieces are the custom installations from artists like Sam Stubblefield that help us take the data and the design into another level of experience and interpretation.

For example, the exhibit opens with one of Stubblefield’s multimedia installations—a video projection and soundscape that uses brain waves to build a collective portrait, reflecting the growing trend to monitor human health with digital devices. The introductory gallery also features sections on Information Graphics, Monitoring the Body, Social Distance, Mutual Aid, and background about MASS Design Group and the work of its COVID-19 Design Response team.

Looking ahead, what’s one goal or hope you have for the healthcare design industry in 2022?

That the industry sees its role as not just effectively shaping buildings from complicated policies and guidelines, but as the agent that will transform architectural thinking and typologies in the world. That, historically, has been the case, and I think it will be again after the pandemic.

Anne DiNardo is executive editor at Healthcare Design. She can be reached at anne.dinardo@emeraldx.com.